Welcome to part 1 of a 3-part series on WHAT we train. We’ll be exploring skill development, conditioning, and strength building in this series. If you understand WHAT each component is, and HOW it affects our training, you’ll understand more of the WHY behind our workouts. While each component affects and intersects with the other two, for the purposes of understanding, it’s helpful to break each one out individually. Enjoy!

What We Train: Part 1 – Skill Development

by Erik Castiglione

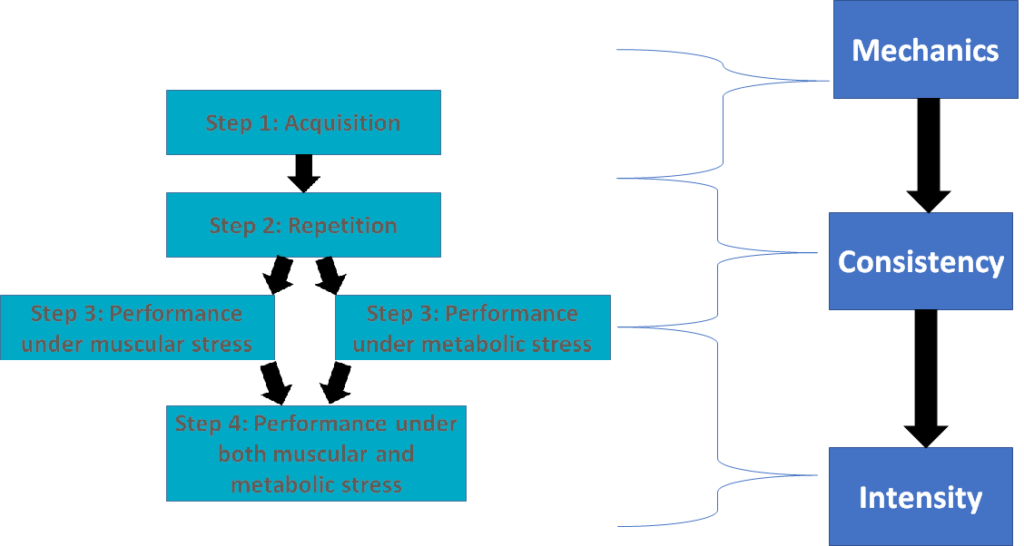

Skill development – it’s a huge but often overlooked component of fitness. What are some common CrossFit skills? Obviously, every advanced gymnastics movement comes to mind (butterfly pull-ups, muscle-ups, handstand walking, etc.). However, pacing, max effort lifts, and barbell cycling are also skills. Skills are neurological by nature – they require us to develop specific neural pathways, so that our bodies move properly. We can develop them through PRACTICE. This should be evident when we look at the skill development hierarchy:

To better illustrate this hierarchy, consider the muscle-up. It’s skill day, and after months of drills, you hop up on the rings and FINALLY get your first one. Congratulations! You have just acquired this skill. Then, a few days later, you decide to get it on video. You hop up, but no matter how you try, you just can’t get a second muscle-up. Was your first one a fluke? No, you just haven’t reached step 2 yet. So, you practice more drills, put them together, and then once again you’re able to get a muscle-up. You’ll get to a point where you can always get 1 muscle-up when you first walk into the gym, and eventually, you’ll be able to do sets of 2, and then 3, and so on. This is step 2, repetition.

Now, let’s say when you’re fresh, you can always knock out a set of 2. But, in an EMOM workout of sit-ups, push-ups, and muscle ups, you fail after round 1. What happened? Well, your core and arms are fatigued, and prevented you from executing a muscle-up. With more practice, you’ll be able to perform a muscle-up even when the muscles involved in the movement have been stressed. Or let’s say your workout is a max effort 1-mile run, followed by max muscle-ups, with a 10-minute time cap. You PR your mile time, but the remaining minutes are spent swinging aimlessly on the rings. Try as you might, you just can’t get up and over. In this case, you’re under metabolic stress, and it interfered with your muscle-up ability.

With continued practice, mixing muscle-ups in various circuits and workouts, you’ll get to a point where you can do them in any workout. When you can perform them while your muscles are screaming and your lungs are burning, you have truly mastered the muscle-up. This is step 4.

This model also fits nicely with the CrossFit mantra “mechanics, consistency, intensity.”

This is all well and good, but why do we care? Because we can go beyond any one movement, and apply this model to EVERY movement, no matter how basic. When you approach mastery of a movement, you are at your most efficient. Have you ever performed a snatch and had the weight fly overhead almost effortlessly? Imagine if every one of your reps felt that way. Now imagine you have a workout involving many snatches. How much energy would you save if you performed every rep that way, as opposed to losing your balance, or fighting to get into a full depth squat?

Now let’s get even more basic and look at two of our cyclical movements, rowing and running. Do you have one you prefer? Can you row at a decent clip for multiple intervals, but find yourself getting winded by the shortest run? Once again, it comes down to movement proficiency. If I am a proficient rower, my form is solid, and I get the most power out of my stroke while exerting the least amount of energy. If I’m not, I get little power transfer from my lower body to my upper body, and I’ll be bleeding energy while getting nowhere fast on the rower. The more PROFICIENT you are, and the longer you’re able to maintain your form, the more EFFICIENT you’ll be. Inevitably, if we go on long enough or perform enough repetitions in a workout, we expect to see some degradation in form because our bodies only have so much capacity. But the better we are at a movement, the longer we can prevent this from happening.

In mixed modality workouts, we are often limited by our movement proficiency. Consider the quintessential CrossFit workout, “Fran.”

The best athletes in the world are proficient enough at thrusters and pull-ups that they can go unbroken through this workout with ease. They make it challenging by moving faster. Of course, that brings up the topic of conditioning, which we’ll get into next week. Ignoring that for a second, and just focusing on efficiency and proficiency of movement, think about your own thrusters and pull-ups. Can you cycle a barbell efficiently enough to go unbroken through your thrusters? Are you able to do 21 pull-ups, then 15, then 9? Most people, even if they can go unbroken on one or the other, cannot do both. So, we’re forced to break. Eventually, the goal is to go unbroken and turn the workout into a sprint. We must develop our barbell cycling and pull-up skills enough that we’re able to do this. Until then, we don’t get the metabolic benefit of this workout, and must develop our ability to sprint through other, simpler WODs.

Finally, let’s consider strength. We’ll be exploring it in depth in a later part of this series, but for now we’ll stick to the neurological component. We talked about the snatch above, so let’s revisit it. It’s your first day learning the lift, and it just feels awkward and unnatural. The weight flies out in front of you, and you’re not able to drop quickly under the bar. As such, you’re severely limited in the amount of weight you can manage. After a month of practice, however, you hit your positions on the way up, the bar turns over correctly, and you’re able to drop under it to catch it. Weight that seemed impossible now flies up overhead. For the sake of argument, let’s assume your other lifts haven’t changed, and you haven’t built any additional muscle. Therefore, you haven’t grown stronger per se, but you’re still able to lift more weight. How is this possible? You became a more efficient lifter. Your bar path is more correct, you’re recruiting more of the muscle you do have, in the correct order, and your timing is better. In other words, your skill as a lifter has increased.

This result is not unique to the snatch; it can happen with the simplest of movements, like the bench press. Each lift is a skill. As you master it, you can lift more weight without changing yourself physiologically. As a brand new CrossFitter, you may have noticed tremendous gains in your lifts, which slowed down over time. Your newbie gains were largely a result of the neural adaptations associated with learning new movement patterns. When skill improvement alone won’t help you lift more weight, it’s time to get stronger. We’ll cover this in part 3. For now, I hope you can see how important skill development is, how it influences both strength and conditioning, and why we must practice all movements. See you in the gym.