Taking the Leap

by Erik Castiglione

Last week we talked about the Law of Accommodation, and how if you do the same thing repeatedly, you get diminishing returns. We combat this by continuously challenging ourselves, both in our strength work AND in our conditioning. At the same time, we need to make sure we don’t overdo it or we won’t be able to recover. So, how do we know when it’s worth taking the leap?

Well, a lot of the work is already done for you. We design our program around intensity regulation. This manifests itself in several ways. In our strength work, we have heavy days, volume days, and speed days for our powerlifts. For the classic lifts (i.e. snatch and clean), we alternate the full lifts with partial lift variations, increase and decrease loads based on our other strength work, and generally work to keep everyone fresh. For the most part, if you follow the program, you’ll make progress.[1]

When it comes to conditioning, it’s not quite as simple. We mix multiple movements and modalities, and since everyone is different, we don’t generally prescribe percentages or time caps. Instead, we tailor the workouts to each athlete, based on what we’re training in that specific workout. An athlete with a history of strength training likely has excellent high-end strength, but not great endurance. This athlete probably doesn’t do well trying to crank out reps at over 80%. Conversely, an athlete with a history of endurance training probably doesn’t have great high-end strength, but is excellent at hitting 90% for multiple reps. Therefore, we don’t base metcons around percentages, and if we do give you them, they’re just guidelines.

Let’s look at a couple of recent workouts to get a clearer picture:

WOD 1:

5 Rounds, Each for Time:

500m Row

15 KB Swings (70/55)

10 Jumping Ball Slams (30/20)

Rest 4 minutes between rounds

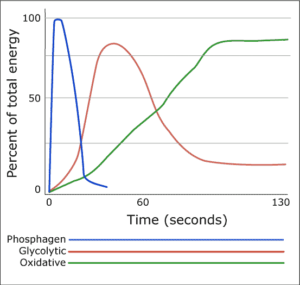

The goal of this workout was to sprint through each round, preferably unbroken. None of the movements are technically complex, so the limiting factor was not your strength or technique, but your ability to breathe when pushing as hard as you can – otherwise known as your anaerobic threshold. As those of you who did the WOD may well remember, training this modality HURTS and leaves you feeling dead for the rest of the day. In workouts like this, the work time does matter, and we want to cap it. Going too long causes the body to use a different energy pathway from the one we intend to train.

Now, let’s compare this with another recent workout:

WOD 2:

4 Rounds for Time:

500m Row

30 Push-ups

1 Rope Climb

In this workout, the limiting factor is the push-ups, so we’re training muscular endurance through high volume calisthenics. In this case, time domain becomes largely irrelevant. High volume is also going to look different for each athlete, based on their chosen range of motion. If Athlete A is advanced, they may get away with sets of 10+ push-ups at full ROM and finish the workout in under 15 minutes. Athlete B, on the other hand, may be able to do sets of 10+ scaled push-ups, but only sets of 4-6 with full ROM. This would be a good opportunity for Athlete B to take the leap and attempt the workout with full ROM push-ups, even if they take significantly longer than Athlete A.

Now let’s look at the quintessential CrossFit workout, “Fran.”

“Fran”

21-15-9

Thrusters (95/65)

Kipping Pull-ups

In an ideal world, “Fran” is done unbroken, as fast as possible, and takes under 3 minutes, similar to a single round of our previously discussed WOD 1. However, both thrusters and kipping pull-ups rely greatly on movement proficiency. Furthermore, to move the prescribed weight, athletes must have a requisite level of strength and muscular endurance. This creates much more room for variability amongst athletes than a simple test of wind or muscular endurance. Let’s trace the evolution of an athlete from on-ramp to advanced:

- On-ramper: performs “Fran” with an empty bar and jumping pull-ups.

- Beginner athlete: uses 50% of prescribed thruster weight and jumping pull-ups.

- Intermediate athlete: uses >50% of prescribed thruster weight, and kipping pull-ups in small sets, scaling volume if necessary.

- Advanced intermediate athlete: uses prescribed weight and kipping pull-ups, but breaks into manageable sets.

- Advanced: performs the entire workout as prescribed, unbroken, in under 3 minutes.

There is A LOT of room from step to step, as anyone who’s ever performed “Fran” can attest. We’ve had some on-rampers finish “Fran” in under 6 minutes, the first time they perform it, and others take upwards of 8. When they progress to step 2, their times slow down significantly. Similarly, when someone first learns the kipping pull-up but can’t perform high volume sets, it’s going to take them significantly longer than someone who can do bigger sets. When you first take these leaps to harder scalings, it is OKAY to take longer than the “goal” time; it’s the only way to learn and grow. It is our job as coaches to advise you and provide you with the space to do this.

There is a school of thought that believes athletes should perform a 3-minute bike sprint rather than a scaled version of “Fran”, because that’s the only way to get the metabolic “stimulus” of the WOD. If you aren’t allowed to attempt it, how will you ever develop the necessary movement proficiency? Furthermore, how would you feel if you were segregated from the rest of class and put on a bike, instead of doing thrusters and pull-ups? Finally, since we can train the same metabolic capacity with a workout like WOD 1 above, we can afford to have you challenge yourselves in workouts with more advanced movements. It’s important to view each workout as part of a bigger picture, and not just a stand-alone event.

We’re here to push you to be your best self. Not sure what the goal of the workout is, or how to scale? Talk to your coach and come up with a personal goal and strategy. That’s why we’re here for you. See you in the gym.

[1] Adaptation is based on stress regulation. We try to control stress inside the gym as it pertains to training, but it is impossible for us to regulate your stress OUTSIDE of the gym. Sometimes, life stress carries over and affects your training. We can adapt the program as needed when this happens, but cumulative stress can prevent progress in the gym.